- Body

Plant communities on rangelands typically are composed of a mixture of grasses, forbs, and shrubs. Some rangelands, such as many ponderosa pine forests or pinyon-juniper woodlands, have an overstory of trees and an understory of grasses, forbs, and/or shrubs. All plant communities, regardless of their location, change across time — a process called plant succession. The changes may be in species composition, life-forms (grasses, forbs, shrubs, trees) and life cycles (annual, biennial, perennial); the abundance of each species; the relative proportion of the life-forms present; the size, density, shape, or arrangement of plants (structure); or combinations of these features.

Vegetation change involves both the direction and the rate of change. A plant community can move toward more desired or productive communities or toward less desired communities. The former can be considered as management opportunities and the latter as hazards that should be avoided. Understanding plant succession is important because the composition of plants within plant communities has three important influences:

- How landscapes function — for example, water cycle, nutrient cycle, soil formation,

- The type and amount of products or resources and services society can develop and produce, and

- Identification of management opportunities and hazards.

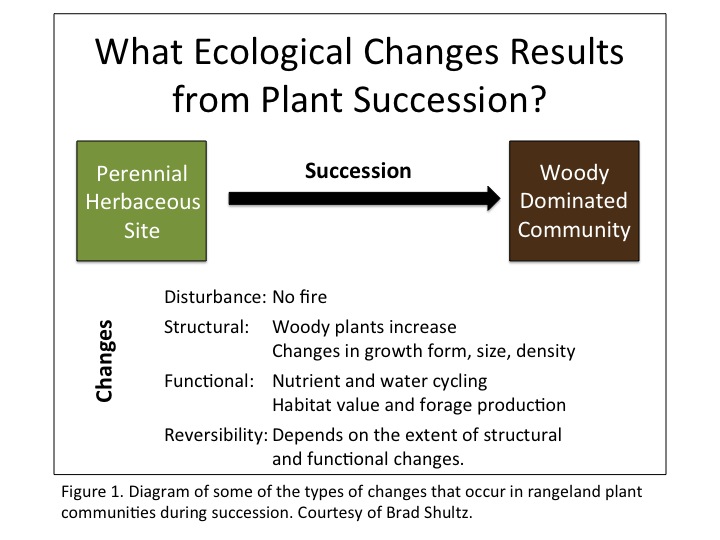

Figure 1 (below) shows some of the ecological changes that result from plant succession across several to many decades on a sagebrush-bunchgrass rangeland.

Periodic fire is the typical disturbance on shrub-grass rangelands that maintains the balance between the perennial grasses and forbs (perennial herbaceous) and the woody shrubs and trees. This is particularly true for shrubs that do not sprout after a disturbance. Fire removes the non-sprouting shrubs and permits an abundance of other, more fire-adapted species. The lack of fire eventually results in shrub-dominated communities and a corresponding decline of the other species. The shift from a predominately perennial herbaceous life-form to woody species changes both structural and functional components of the ecosystem. The key management question is: Can the change to shrub dominance be reversed, completely or partially, to meet management goals and objectives for desired resources?

Among the important concepts in plant succession on rangelands are the ecological site, community resilience, and community resistance. An ecological site is a unique, identifiable, and repeatable patch of vegetation on a landscape. It has specific (homogeneous) biological, physical, and chemical characteristics and the potential to produce a distinctive kind and amount of vegetation. An ecological site is a product of all of the environmental factors that influence the development of soils and vegetation, including disturbance regimes. Vegetation on an ecological site is not static and can be one of several seral communities, with the same species present but in different amounts. If the biological, physical, or chemical conditions that create an ecological site change, the site can degrade to a different bio-physical state. Resilience refers to the ability of a plant community to return to prior composition and structure after a disturbance. Resistant communities, or one of their seral stages, occupy the site after it has been disturbed. Resistance refers to a plant community’s ability to avoid being changed from its current state.